To make Trump counties blue again, Democrats have to actually do something

It's not simply a matter of telling people to shut up

Welcome to the big Monday morning edition of Progressives Everywhere!

(Hey, it’s a long weekend for me.)

As Democratic lawmakers squabble over whether they should help working people or wealthy nihilist lobbyists, there is also a debate raging in the niche ecosystem of political commentariat Twitter and the Beltway publications that fuel and react to Twitter’s loudest voices. I’m generally much more focused on direct action and policy than on philosophical debates, but our big story this week about the future and fate of the Democratic Party encompasses both of these debates.

But first, thank you to our latest crowdfunding donors: Vera, Barbara, Ellen, and Mary Beth!

The early stages of grief that followed the 2016 election never fully dissipated for many rank and file Democratic voters. Even today, there is a pervasive disbelief that Hillary Clinton could have lost to the buffoonish bankrupt reality star who spoke a narcissistic dialect of gibberish and had been so far behind in the polls. How could it have happened? What did people see in Donald Trump?

Soon after that election, a squadron of journalists flocked to diners across rural America, heralding a revolving door of visiting reporters determined to give voice to the forgotten blue collar American that had fallen under the sway of the blustery snake oil salesman president. They sought to better understand the disconnect between professional poll projections and election results, and one of the earliest stories of the genre, this New York Times report from a small town in eastern Iowa, noted that many union members were proud to display MAGA yard signs. This was supposed to epitomize the profound political shift, and yet like most of the dispatches from that four-year stretch of domestic anthropology, the piece largely suggested that cultural issues were the main culprit.

To Richard Martin, a consultant and long-time Democratic campaign veteran, the phenomenon couldn’t just be chalked up to a bunch of “deplorables” emerging to vote for the first time in 2016. In a way, it was actually much simpler than that.

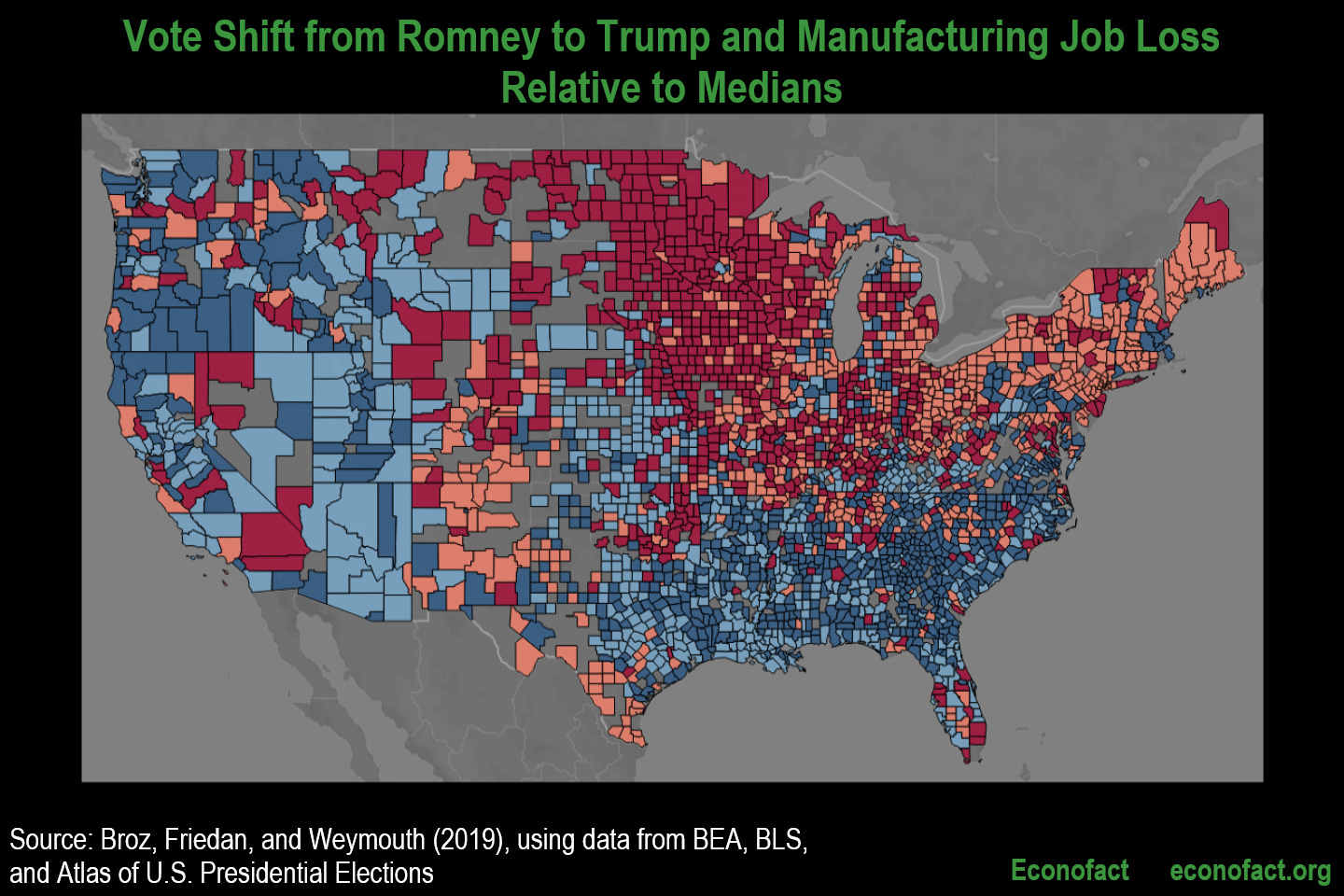

“You could see there was a very strong correlation between the declining manufacturing base and a strong vote for Trump,” Martin tells Progressives Everywhere. And the numbers bore him out.

After segmenting out the populations of 10 states in the Upper Midwest (including Upstate New York), Martin decided to look at what he called midsized manufacturing counties. He defined them as counties that contain several towns with more than 35,000 residents, are not part of any big metropolitan areas, and have a local economy that consists of least 13% manufacturing jobs.

The results were ugly: In 2016, Hillary Clinton lost these midsized factory counties by a whopping 814,690 votes, a wild swing from President Obama’s 105,848-vote margin of victory in those same counties. She also got crushed in smaller manufacturing counties, which had no towns of more than 35,000 people and accounted for 480 of the 853 counties in the states that Martin studied.

The cratering in manufacturing counties overwhelmed the gains that Clinton made for Democrats in the cities and suburbs, cost her close races in Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, and ultimately lost her the election. It wasn’t hard to figure out why, either.

Clinton was trying to follow an Obama administration that had overseen a net loss of more than 300,000 manufacturing jobs. While that number was attributable largely to the Great Recession, job growth in the sector was almost zilch in 2016, and by that fall, the media was noticing that five million American manufacturing jobs had been lost since 2000 — a storyline they picked up thanks to Donald Trump.

“Trump planted seeds in angry soil and those seeds were able to take root in angry soil because he was the first nominee from one of the major parties to stridently come out against unfettered free trade since forever,” Martin notes. “He’s like one of those cancer-sniffing dogs. In his own unique and crude way, Trump identified the problem: Jobs going to China at a record rate and dictatorship economies being allowed to run crazy with free trade. But like the dogs and cancer, he’s not qualified in any way, shape or form to solve the problem.”

Martin points out Trump’s first presidential debate performance as a key moment in the campaign, even if it hadn’t been heralded as such at the time.

“In that debate, he did not mention building a wall with Mexico even once, but he talked about free trade problems with China 10 times,” Martin says. “He just came out guns blazing on that first question, attacking Hillary on the trade issue.

Sure, it was under Republican President George W. Bush that most of those jobs had been lost, but manufacturing wages were under Obama and it was Clinton name that was most associated with the slide, especially amongst blue collar manufacturing households. Bill Clinton was the president that passed NAFTA and won China’s admission to the World Trade Organization, which opened the door to the devastating period of outsourcing in the 2000s. Hillary, though very much her own woman, was involved in policy to an unprecedented degree during her time as First Lady.

Unfortunately, a mix of loyalty to the Clintons, financial vested interests in leadership, and the party’s bitter internal divide made Martin’s assessment less than popular with the people he’d hoped to persuade.

“In 2017 and 2018, I tried share this information with people in Iowa Democratic Party circles and I was very discouraged,” he says. “Because what I was trying to say seemed to run counter to what people wanted to believe. People wanted to believe that Trump won in 2016 because some Democrats stayed home because they were Bernie fans and didn't like Hillary, and that Trump turned out all these racists.”

There are certainly racist Trump supporters, and Hillary Clinton continues to be the target of irrational American animus, but those couldn’t be the only takeaways. The 2020 election results bolstered Martin’s economic argument. Of the 537 manufacturing counties that shifted to Trump, a full 71% of them suffered a loss of manufacturing jobs between 2001 and 2019, and just about none of them flourished. Further, the more jobs that were lost, the more dramatic the move toward the GOP.

While Biden didn’t perform quite as catastrophically poorly as Clinton in the manufacturing counties, he still got creamed, losing 2.5 million votes in small and midsized manufacturing counties. More than anything else, it was increased margins of victory in cities and suburbs that pushed Biden just over the finish line in these states.

Democrats specifically targeted suburbs in both 2018 and 2020, and in both cases, they celebrated more victories than losses on Election Night. As a result, there’s a temptation to ask why they should even bother manufacturing counties — can’t they just continue to rack up votes in more densely populated areas?

Well, in addition to the moral bankruptcy of casting aside a broad swath of the population — these counties make up 40% of the ten states Martin studied — cutting regions loose are also a terrible electoral strategy. In fact, the combination of this country’s vast size, unequal population concentration, and antiquated system of representation means that manufacturing communities are becoming even more politically important, even as they shrink and suffer.

The more these communities turn solid red, the more seats in Congress and state legislature that Republicans are guaranteed to win, especially given their ability to gerrymander preferable districts right now.

The good news is that the presence of empty factories isn’t in and of itself the harbinger of a hard Republican shift.

In fact, there were 19 manufacturing counties that saw Democratic vote share growth. The difference was that two-thirds of those counties also happen to be located much closer to cities or four-year colleges than the other manufacturing counties, which in turn meant that they were more likely to have diverse economies and more plentiful job opportunities for former factory workers, newcomers, and young people.

Similarly, while the suburbs have lost over 150,000 net manufacturing jobs, their proximity to cities also allowed them to weather those losses and go further blue in response to Trumpism. Further, the few metropolitan areas that lost factory jobs and shifted slightly to the GOP experienced a relatively high rate of economic depression, which underscores the link between the two.

Without solid, good-paying alternatives for lost manufacturing jobs, communities generally experience a terrible ripple effect. The steep decline in union membership (nearly 500,000 members in these 10 states between 2010-19) strips people of health insurance, leads to the closing of hospitals, devastates the rest of the local economy, and fuels a drop in health outcomes. This catastrophic domino effect also has serious political consequences.

As Martin notes in his study, there were 309 manufacturing counties that suffered both factory job losses and declines in residents’ health between 2012 and 2020, and those counties provided a million new GOP votes. People did not flock to the GOP just because Trump promised to bring back manufacturing jobs and the lives they offered, but the disaffection of the unemployed and desperate does obviously have severe political consequences.

“This isn’t irreversible,” Martin insists. “I'm not saying that we can bring back all those manufacturing jobs, but I am saying that we can pursue policies that encourage the creation of value-added, higher paying jobs, so you can buy a house and make that mortgage payment comfortably and raise a family. What we cannot do is allow rich people to not pay taxes and put an increasing tax burden on working class people and expect that if we don't invest in our infrastructure that everything's gonna be okay.”

Democratic politicians should also be on picket lines with the workers fighting big and greedy corporations, not just occasionally tweeting their support. Imagine what kind of difference it would make if they came through the workers at Kellogg’s in Michigan and Pennsylvania or the many John Deere workers likely going on strike this week. Many of the unionized manufacturing jobs that do remain are exhausting and exploitative due to the leverage companies have from free trade agreements and weak labor laws, and a commitment to reversing that dynamic would go a very long way.

That brings us to the present moment, with the Democratic caucus battling over what to include in the final version of the Build Back Better social spending bill. The best version would create the largest re-orientation of the federal government since the Great Society, with an expansion of public services, new programs to subsidize a better standard of living, enhanced workers rights, dramatically improved health care, and money for millions and millions of good-paying jobs.

But there are forces within the party trying to severely limit the bill’s most generous and transformative provisions, under the guise that doing so is the “moderate” position and thus more likely to be popular with right-leaning voters.

The idea that doing less to create jobs and improve the lives of people who defected from your party is an absurdity; just ask this Trump voter in Arizona or the whole of West Virginia. It’s really the sort of short-sighted argument that only a lobbyist-bought politician could make, which is why the online political press feedback loop is so concerning right now.

In stories that ran in Politico and the New York Times last week, influential data guru David Shor was given largely free rein to trash the progressive elements of the Democratic Party, which he did by insisting that activists and young people force Democrats into language and policies that harm them in elections. The solution that Shor most frequently offers in both his Tweets and in consultation with Democratic politicians is that they downplay and even silence conversations about race and other “cultural” issues, which he justifies by pointing to research suggesting that activists’ calls to defund the police during the Black Lives Matter protests hurt Democrats last November.

That there were just as many studies that found the slogan had no significant impact on election outcomes is seemingly irrelevant.

Shor would rather see Democrats embrace “popularism,” which is code for having white politicians run the party and talk only about issues that prove popular in polling. Putting aside the fact that ignoring civil rights is both immoral and idiotic for a party that counts Black voters as its most loyal supporters, it also represents a regression to the past 30 years of Democratic politics. As Martin research lays out, those policies have not worked out so well, economically or politically.

The evidence that Shor cites isn’t exactly convincing, either. In 2015, he noted that college-educated liberals working for Obama saw economic inequality as the most pressing issue facing the country, while voters in test groups listed inflation and war as their biggest concerns. But foreign policy has not shaped elections since at least the Reagan era, and judging by today’s economic misery and the political turbulence it drives, it’s hardly damning to say that they were ahead of the curve. Imagine if campaigns had actually paid attention.

Further, Shor told the New York Times that Hillary Clinton “lost because she raised the salience of immigration, when lots of voters in the Midwest disagreed with us on immigration.” Yet as Martin’s research shows, Trump focused down the stretch on free trade and the loss of manufacturing jobs, not immigration. While immigration is often a misguided irritant for people who have lost their jobs, it was keying in on the source of the anger that proved successful.

Policy consensus tends to shift far faster than political labels and identification. Shor and his cohort often note that Democratic voters most often call themselves “moderate,” but that self-identification is miles away from what the political class considers “moderate.”

For example, Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, and Rep. Josh Gottheimer are often described as moderates in the press, but they’re really right-wing corporate sell-outs, working to oppose the most popular policies in the Build Back Better plan.

Meanwhile, it’s the vocal progressives — including and especially the Squad and other women of color, like CPC chair Rep. Pramila Jayapal — that are actually trying to pass these remarkably popular programs. And most of these programs, along with the demands for racial equity and economic reorientation behind many of them, are necessary due to the total failure of the neoliberal order that white “moderates” installed.

This is not to say that economic progress alone will be enough to win back many of the manufacturing county voters. There is undoubtedly a heavy element of racism in Trump’s nationalist appeal, which is why Nazis, modern Klan members, and the worst police officers are amongst his most passionate supporters. And Martin’s study does find that the few manufacturing counties with more than 15% people of color were largely able to resist the full pull of Trump’s lure.

But Martin also pointed out to me that many of the most vocally pro-Trump midsized manufacturing counties voted twice for Obama, and given those places’ relatively low demographic turnover rate, it’s hard to conclude that race was the only factor. Deliberate disinformation, tribalism, a slanted media, and other items also play a role.

So no, providing Medicaid benefits, childcare, and jobs building solar panels isn’t going to flip everyone. But the political realignment of the suburbs means that Democrats do not need to win back every single vote. The political goal in these manufacturing counties needs to be winning enough votes back to make gerrymandering far more difficult, regularly flip an increased number of swing districts, and disarming the appeal of toxic nationalist Trumpism by making peoples’ lives better.

Trying to tamp down demands for equality and equity will never work, especially not when doing so is meant to cater to the forces of hate and cynicism. Republicans and the right-wing media will always find race bait to exploit, even if they have to invent it themselves (see: the astroturf campaign to elevate the “threat'“ of Critical Race Theory). Doing less for people is political folly. Instead, a government that fosters a society that provides true economic opportunity and social support will create political stability and a winning electoral coalition.

Wait, Before You Leave! Join the Team!

Progressives Everywhere has raised over $6.2 million dollars raised for progressive Democratic candidates and causes. Isn’t that cool?

All of that money go to those candidates and causes and I don’t get a dime of it. And because the only way progressives will be able to rescue this country is by creating their own sustainable media ecosystem, I need your help.

I’m offering very low-cost premium membership to the Progressives Everywhere community, which will help make this project sustainable and allow it to continue growing. It’ll also help me hire another writer/researcher to make this newsletter even better. If you become a member of Progressives Everywhere, you’ll get:

Premium member-only emails featuring analysis, insight, and local & national news coverage you won’t read elsewhere.

Exclusive reporting and interviews

More coverage of voting rights, healthcare, labor rights, and progressive activism.

Personal satisfaction

Here’s a recent example of the reporting we do in premium member newsletters:

You can also make a one-time donation to Progressives Everywhere’s GoFundMe campaign — doing so will earn you a shout-out in an upcoming edition of the big newsletter!