Republicans turn Medicaid unwinding into class war against children

Trick questions and confusing instructions push kids and their struggle in parents to the edge.

Welcome to a Monday night edition of Progress Report.

Tonight we’ve got a big piece on what I see as the most important, least talked-about ongoing news story in the country. I want you to read it, so I’ll make this introduction extra short.

I spent last Friday morning in the far-reaches of south Queens, covering a Teamsters rally in front of the massive UPS depot and sort center next to the Kosciuszko Bridge. With a strike edging closer, Teamsters locals have begun to mount practice strikes, which mix light logistics rehearsal with loud shows of strength from both union members and supporters from the community.

Talking to workers is always my main focus, but on Friday I was also on the scene to follow Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as she met with union leaders, conversed with rank-and-filers, and revved up a crowd of workers in the hot morning sun.

We’re working a big piece from the event over at More Perfect Union. Until then, here’s a bit of pre-rally footage with AOC and Teamsters local 804 president Vinnie Perrone, one of the more outspoken leaders in the country.

The piece at MPU will have far better footage, in terms of visuals and audio, but I figure it’s always fun to see behind the curtain a little bit.

On, now onto tonight’s main story.

Arkansas’s Department of Health Services announced on Monday that it kicked 77,000 people off of Medicaid in June, the third month in a bureaucratic bloodletting is wreaking havoc on the state’s poorer communities.

It was Arkansas’s largest Medicaid purge since April, when the Biden administration lifted its two-year moratorium on booting those who no longer qualified from the low-income healthcare program. Whereas it took 24 months for the state to add 230,000 new beneficiaries to its Medicaid program, Arkansas officials needed just three months to strip 210,000 people of their health insurance.

Now verging on halfway through July, it’s likely that the state now has fewer people on Medicaid than it did when the pandemic began. The number of enrollees should only continue to plummet, and not because the nation’s fifth-poorest state has suddenly experienced a rapid economic upswing.

In an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal defending her state’s rapid abandonment of Medicaid beneficiaries, Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders claimed that Arkansans who “ordinarily wouldn’t qualify for Medicaid are taking resources from those who need that safety net.”

But the state’s mass-disenrollment has hardly been about ensuring that Arkansas’s most financially vulnerable are provided comprehensive care. Instead, nearly 75% of the state’s purged beneficiaries thus far have been stripped of their health insurance due to technical problems with their case files. Given the impenetrable legalese of the paperwork required for Medicaid renewal and the state’s half-hearted effort to get in touch with beneficiaries at risk of losing their insurance, the technical difficulties have often felt more like inevitabilities.

“I think that they're being pushed to cut the rolls, " says Neil Sealy, a healthcare-focused organizer for Arkansas Community Organizations. “I think politics is totally involved. The right believes that this is like welfare, and in their mind, we need to cut the big government. So they're using this as a way to trim the rolls; that's pretty clear.”

Sealy has had a front row seat to a brutal mass blood-letting, with more than 10% of the state’s residents losing their health insurance in what seem to be increasingly frustrating and unwarranted circumstances.

“I got a call from a daycare worker yesterday, and the state just can't get her information right, so one of her children is on ARKids [the state’s Medicaid program for children], but apparently the other one was not renewed,” Sealy says, outlining a typical recent case. “She called the Medicaid call center and didn't get an answer. She’s gone down twice to the local DHS office. Turned in stuff, got it stamped, but it's still not changed. How many thousands of people are having to deal with this?”

Sealy has been inundated with horror stories to troubleshoot, including one women who was eight months pregnant when she suddenly discovered that her Medicaid expiring. For those who have received the appropriate redetermination forms, trying to follow their instructions, which read like a bureaucratic Choose Your Own Adventure, has often proven futile.

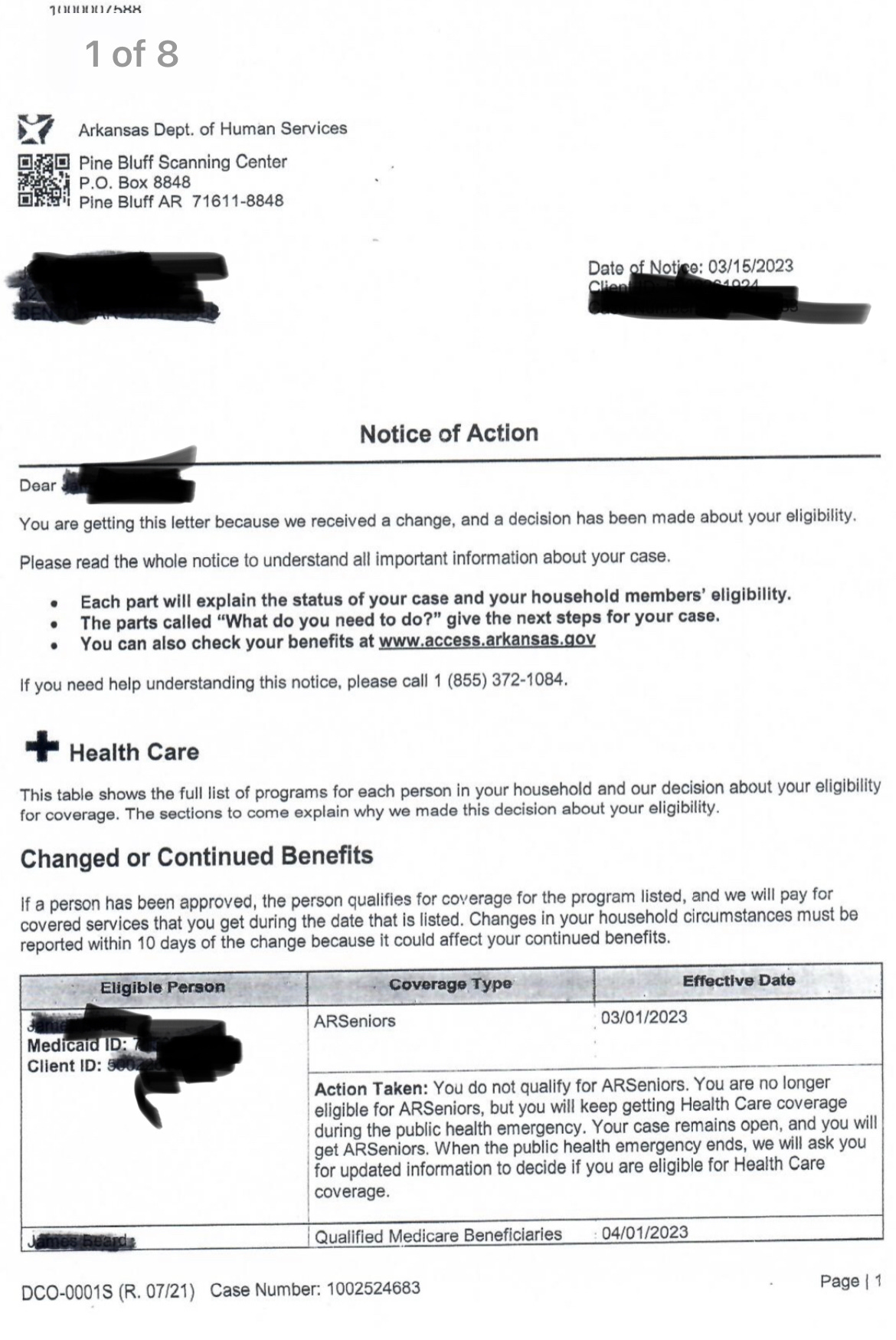

Look at the paperwork below and tell me that you can parse whether rhe recipient has qualified for Medicaid and what they should do next.

The Arkansas Division of Health Services is not likely trying to confuse people — these are career civil servants — but it’s screamingly obvious that leadership did not put emphasis on usability or continuing people’s care. As Sealy explains, new challenges, often based in unexpected government policies, frequently pop up for even the most diligent, whether it’s unrelated child support issues or Medicaid files left open in states where they haven’t lived in years.

How we got to this point makes it all the more distressing.

Early on during the Covid pandemic, as tens of millions of people lost their jobs and hospitals were overwhelmed, the federal government began providing states with additional funding to cover newly qualified Medicaid beneficiaries. The money came with one condition: so long as the nation remained in an official public health emergency, the states were not permitted to remove people from the program.

Thanks to the pandemic-era freeze on disenrollment, Medicaid enrollment grew by more than 21 million Americans, a nearly 30% increase. While qualifying for Medicaid indicates financial distress, the program’s growth ensured that fewer and fewer Americans were falling through the nation’s patchwork insurance system.

For a moment, between the Medicaid continuous coverage clause, the child tax credit, expanded unemployment and student loan pauses, we were looking at a paradigm shift in the way that government organizes our economy and helps Americans care for one another. But that was too much of a threat to entrenched power, so the expansed social safety net was cut through until the bottom fell out.

In December, a federal budget deal codified an April 1st end to the public emergency, providing states a three-month window to organize the messy process of redetermining residents’ eligibility.

The deal permitted a full year to run through the unwinding process, and states were given explicit instructions to make every effort to find ways to either keep people enrolled on Medicaid or help them find new subsidized plans on the ACA marketplace. Arkansas didn’t want or need the grace period; a coalition of nonprofits in the state have been rallying and writing letters since January, but for many Republicans, seeing tens of thousands of poor people lose their government healthcare every month represents a dream come true.

It’s not just happening in Arkansas, either. In Florida, more than 250,000 residents lost coverage between April and May, with June numbers still to come.

“It feels like every month, I lose more and more kids from my client list because their Medicaid is not active,” says one mental health professional in Florida who works mostly with patients on Medicaid. “Now they're telling people who reapply that it can be up to six to eight weeks before things get moving. And so I just don't see kids during that time.”

There were more than five million people enrolled in Florida’s Medicaid program before the unwinding began, including 1.7 million who signed up during the pandemic pause. Both numbers would be far higher if the state were not one of the dozen holdouts that have yet to expand Medicaid under the ACA.

Instead, Florida’s Department of Children and Families went into the unwinding with a pre-prepared purge list of 900,000 people, including 300,000 vulnerable children. There were another 850,000 names on a list of potential Medicaid evictees, and in its rush to disenroll people, Florida has been prematurely stripping grievously ill children of their health insurance as they undergo treatment.

“The very first month, two of my most at-risk clients lost their Medicaid, which was very frustrating, especially because one of them had just had a suicide scare two or three weeks earlier,” the therapist told me. “Her mom immediately called Medicaid trying to get it reinstated — she also needs medication in order to not have these suicidal ideations — and that’s all she did for three straight weeks.”

The federal government has signaled deep concern over the rapid, sloppy purges, largely in the form of letters that urge states to knock them off. It’s also offered shortcuts and ways to either renew or at least delay the terminations of beneficiaries who prove hard to contact.

As of last week, Ron DeSantis’s Free State of Florida was one of just two states that had yet to accept any of these offers, instead electing to provide residents with total freedom to lose their access to medical care.

It goes beyond federal help, too. Florida, which has seen a massive population shift due to skyrocketing housing costs, waves of people moving in from out of state, and growing homelessness, has declined to provide any grace period to folks that were caught off-guard.

Arkansas’s original decision to expand Medicaid was driven by then-Gov. Mike Beebe, a moderate Democrat who convinced Republicans to back the program by converting federal dollars into vouchers for comparable, regulated private health plans. His departure set the stage for a Republican trifecta shortly thereafter, and Republicans have since spent an inordinate amount of time trying to make Medicaid as inaccessible as possible.

In 2018, the state won permission from the Trump administration to impose work requirements as a condition of receiving the benefit. Framed as a way to get people into the workforce, the extra bureaucratic hurdle had no tangible impact on employment rates. Instead, it simply resulted in 18,000 residents losing their health coverage and becoming mired in debt and medical hardship. A federal judge found the new rules so detrimental to the program’s goals that he ultimately ended the experiment.

In 2021, Republican legislators voted to require the state to flush out ineligible Medicaid beneficiaries in just six months’ time, or less than half of the 14 months that the federal government was offering at that time. The state’s Department of Health Services was ready to get started immediately, and spent much of 2022 in purge mentality, even after the public health emergency was extended indefinitely.

DHS put together a public awareness campaign that included ads on the radio and social media; healthcare providers were also sent lists of at-risk beneficiaries. Phone calls and texts were also made to beneficiaries as the deadline approached. The effort was earnest and valiant, but as one Medicaid expert in Arkansas explained to me, it was largely incompatible with the intended audience.

Poor people are far less likely to receive regular care from doctors, limiting opportunities for in-person reminders from providers. They’re also far less likely to have steady housing, so in many cases, Medicaid recipients never received their renewal paperwork. And all along the way, Arkansas Republicans, including state Rep. Jack Ladyman, have shrugged their shoulders at the prospect of hundreds of thousands of Arkansas losing their health insurance.

While Arizona and Indiana have also been churning out policy cancellations, other states have been far more cautious in their approach and focused on retaining as many beneficiaries as possible.

In New York, the state plans to use the maximum 14 months to complete the unwinding process, with all of that time earmarked for working to maximize outreach, data-sharing for automatic re-enrollment, real-time determinations and bolstered staff to help both beneficiaries and those who will need help finding free or subsidized plans on the state exchange. Though it has nearly three million more Medicaid enrollees than Florida, New York is projected to lose exponentially fewer beneficiaries.

Michigan decided to give an additional month to residents who were supposed to hand in their paperwork by June 30th.

Minnesota has been even slower to act on redetermination, pushing its very first deadline back to August 1st. At that point, an initial 35,000 Minnesotans will be required to submit their paperwork, and with processing time, it could take until the fall for some of those residents to be declared no longer eligible for Medicaid. At that point, Arkansas will have finished its entire purge, with more than ten times the number of people having been thrown off their health insurance.

Poverty is a policy choice. Inevitability is a policy choice, too.

Wait, Before You Leave!

Progress Report has raised over $7 million dollars for progressive candidates and causes, breaks national stories about corrupt politicians, and delivers incisive analysis, and goes deep into the grassroots.

None of the money we’ve raised for candidates and causes goes to producing this newsletter or all of the related projects we put out. In fact, it costs me money to do this. So, I need your help.

For just $5 a month, you can buy a premium subscription that includes:

Premium member-only newsletters with original reporting

Financing new projects and paying new reporters

Access to upcoming chats and live notes

You can also make a one-time donation to Progress Report’s GoFundMe campaign — doing so will earn you a shout-out in the next weekend edition of the newsletter!

Republicans are so concerned that poor and disadvantaged people, included children, might get a handout and receive some healthcare or a few bucks worth of food stamps they might not qualify for. I'm much more concerned with stopping the massive handouts that the billionaires and major corporations are getting! Then we could fund necessary social programs and cut the deficit !